[Here’s the first in an ongoing series of reviews of all of Lloyd Alexander’s non-Prydain books. To see all posts in this series, click on the “Lloyd Alexander” tag.]

On a Friday morning a year ago this month, I sat down in the barber shop, picked up the paper, and felt a sharp, sudden tap between my eyes. The sensation was odd and yet oddly familiar, though I hadn’t recalled it for 25 years. The last time I felt it, I had been reading a novel by Lloyd Alexander, and the author informed me that someone had died. This time, again, I was struck by sad news: Lloyd Alexander himself had just died.

That weekend, I drove to a secondhand shop and bought up a stack of his novels. While tributes to Alexander began to appear online, I rediscovered the Chronicles of Prydain and read the Westmark series for the first time. Alexander’s worlds were as poignant and as humane as I remembered, but I was newly impressed by his handling of moral and ethical quandaries. I also marveled at his prose style: amazingly concise, with few spare words and no tendency to linger over descriptions. We could all learn a thing or two from Lloyd Alexander about how to “write short,” and how not to be a self-indulgent stylist.

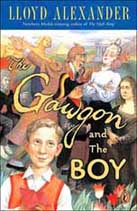

Shortly before Alexander’s death, I had sent him a copy of my own book and received a kind note in reply. That was cool, but stumbling across The Gawgon and the Boy was, I confess, even better. Largely overlooked upon its publication in 2001, this short book with the strange title is the sort of novel that only an author with a proven sales record would ever be permitted to publish.

Unlike Alexander’s other novels, this book is explicitly autobiographical: set in Philadelphia during the 1920s, The Gawgon and the Boy tells the story of eleven-year-old David, whose near-fatal bout of pneumonia leaves him unable to attend school. While David convalesces at his grandmother’s boarding house, his family debates the future of his education:

My heart chilled as they went on calmly discussing my fate. One way or another, I was doomed to be removed from the back alley. A private teacher? One person, face-to-face, with a constant eye on me? Worse than Rittenhouse Academy, where I could hide unnoticed among my classmates.

Aunt Annie, silent until now, put down her cup. In a tone that made me think of the Almighty commanding Abraham to sacrifice young Isaac, she said:

“Give me the boy.”

Aunt Annie is, of course, the “gawgon” of the title, a grim and matronly presence in a boarding house already full of oddballs. Delightfully, Alexander remembers, and can put into writing, how the world looks at eleven:

Not that she treated me with anything less than kindness. To her credit, at Christmas and my birthdays, when my relatives gave me handkerchiefs and underwear, she gave me books. Still, she made me uneasy. Invisibility has its advantages; but when she turned her sharp glances on me, watching me closely, I was no longer the Amazing Invisible Boy. On the contrary, I felt that she could see me very clearly indeed and quite possibly could read my mind. For that reason, she frightened me a little. Or perhaps it was simply because she was very old.

With the Gawgon as his mentor, David lets his education and his imagination intertwine. He and the Gawgon soon journey through Greek mythology, spar with Napoleon in Egypt, consult with Sherlock Holmes, and scale the Matterhorn, where strange, moping poets reside. A fictionalized account of the education of Lloyd Alexander and a loving tribute to the woman who directed it, The Gawgon and the Boy is also, by extension, a tribute to the random bits and pieces of literature and life that shape us, inform us, and later define us.

In fact, The Gawgon and the Boy is so charming, so genial, and so utterly disarming that it comes as a shock when the book turns bittersweet, as David’s education leads him to perceive, with growing clarity, the private pain of the adults in his life. In just 199 pages, Alexander writes lightly about subjects that other novelists spend thousands of pages groping to understand—and, at 77, he still knew how to tap a reader right between the eyes.

In the Prydain books, Lloyd Alexander used heroic fantasy to chronicle the pain of growing up. In the Westmark trilogy, he cast a kingdom in shades of gray to explore, with greater wisdom than most “adult” writers have done, the moral implications of shedding blood in the name of revolution. These series aren’t as different as they seem: at the heart of every Lloyd Alexander novel is, as the author once explained it, a simple concept: “how we learn to be genuine human beings.” It’s a sign of Alexander’s maturity that The Gawgon and the Boy continues that theme not with monsters or tyrants or magical kingdoms, but through a more subdued story that’s no less engaging: how an author-to-be learned to read and love books.

Sometimes, Jeff, I think you’re my evil (or good) twin. Delaware, Charlemagne, now Lloyd Alexander. His Prydain books were formative in my childhood. I’m sad that he’s gone.

LikeLike

Matt, I could sure do a lot worse than to claim you as my smarter, better-educated twin.

One of the best things about Alexander was how prolific he was. Every time I scrounge around a used bookstore, I find “new” novels of his. As great as the Prydain books are, I’m enjoying seeing how his basic decency and moral sense continued to find expression in later novels. Alexander’s mind, which is by no means childish, is a fine place to revisit as an adult.

LikeLike