[This is the second of four blog posts focusing on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s medieval-themed stories. The first post can be found here, the third one is here, and the fourth one is here. If it matters to you, please be aware that these posts about obscure, 80-year-old stories are pock-marked with spoilers.]

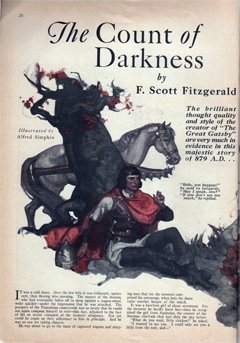

It’s a shame that F. Scott Fitzgerald’s second “Philippe” story begins with an editor’s lie: “The brilliant thought quality and style of the creator of ‘The Great Gatsby’ are very much in evidence in this majestic story of 879 A.D.” Two lies, really: By design, there’s nothing “majestic” about “The Count of Darkness.” Fitzgerald wallows in sketching out civilization at its lowest ebb, but it turns out that his version of the Middle Ages give him more than he’s prepared to confront.

It’s a shame that F. Scott Fitzgerald’s second “Philippe” story begins with an editor’s lie: “The brilliant thought quality and style of the creator of ‘The Great Gatsby’ are very much in evidence in this majestic story of 879 A.D.” Two lies, really: By design, there’s nothing “majestic” about “The Count of Darkness.” Fitzgerald wallows in sketching out civilization at its lowest ebb, but it turns out that his version of the Middle Ages give him more than he’s prepared to confront.

When last we checked in with Philippe in the October 1934 issue of Redbook, Fitzgerald had dropped Ernest Hemingway into ninth-century France, dressing him up as a noble exile-hostage returning from Spain to France to reclaim both land and leadership. It’s now June 1935, and while the story picks up only a day or so after Philippe has rallied a scruffy band of locals, routed a band of Northmen, and invented feudalism in the process, Redbook editors are presuming a great deal about their readers’ ability after eight months to recall any of that.

“The Count of Darkness” opens with the nicest bit of writing in this series so far:

It was a cold dawn. Over the low hills it was iridescent, opalescent, then flowing into morning. The master of the domain, who had eventually fallen off to sleep against a wagon-wheel, woke quickly—under the impression that he was attacked. The prospect of the Tourainian countryside was so lovely that he could not again compose himself to rest—this fact, adjoined to the fact of his so recent conquest of the farmers’ allegiance. Not yet could he count on their adherence to him in principle. And he was no one for taking chances.

That’s far from an elegant paragraph. Fitzgerald tells more than he shows: “iridescent, opalescent” gives us only adjectives, not images; “under the impression that he was attacked” conveys no real sense of alarm; and the pedantic clarity of “this fact, adjoined to the fact” is at odds with Philippe’s groggy restlessness. Still, I can hear faint traces of Fitzgerald in those sentences, laboriously rallying the ghost of his former gifts in a failed effort to set a suitable mood.

But then Philippe chats up a 17-year-old Aquitainian girl, and things get weird:

“What do you want, little chicken?” he asked.

“I wanted to see you. I could only see you a little from the tent, and—”

“Don’t grovel in the dirt, for God’s sake! Get up from your knees!”

“I’m not a man.” She stood and faced him. “How do I know about your habits for gals?”

“There are no habits—I make the habits.”

His eyes had become covetous as he looked at her. “How would you like to become one of my habits?”

“Oh, sire, I would be so glad to be yours—”

“What’s your name, little baggage?”

“Letgarde.”

“Who gave it to you? That Norman?”

“It was my christened name.”

“Come here and see what you taste like.”

After a while he released her with:

“I’ve met worse kids. How you going [sic] earn your keep? Can you get together some stew from the rations in the wagon—if we get up a couple boys to do the heavy stuff?”

“I’ll try it, darl—”

“Call me ‘Sire’! . . . And remember: There’s no bedroom talk floating around this precinct!”

“All right, darl—I mean sire.”

“Well, run along.”

I think we’re supposed to hear the voices of a 1930s gangster and his moll—but are “chicken” and “baggage” 1930s slang, or are they Fitzgerald’s way of sounding “medieval”? In the first story, Philippe was stern and humorless. Is he still being a grim, flinty strongman, or is he flirting here? In The Great Gatsby, several telling moments arise when the narrator elides a potentially revealing or uncomfortable event, so again I saw the old Fitzgerald in the “[a]fter a while he released her” line, which invites us to fill in the blanks—but it’s clunky and obvious and fosters no sympathy for Philippe.

But maybe that’s the point. Philippe’s second act that morning is to find women who can cook and clean for the men in his nascent army. He later addresses what he considers a “minor problem”: “announcing to the half-dozen girls who had been rounded up that for the moment each would be permitted her parents’ hut for the night, but that in the future there would be no marriage permitted in the country save with his permission. He would expect them to choose their mates among his own men.” Later, when Philippe spots a Syrian caravan attempting to ford his river, he proposes robbing the merchants before downgrading his plan to merely extorting the heck out of them. Fitzgerald has a lurid preoccupation with how nasty and brutish people get when civilization shatters. He wants to shock and enlighten the magazine-reading public of 1935, like an Ivy League freshman who comes home at Thanksgiving and has grown so much wiser than everyone else.

But maybe that’s the point. Philippe’s second act that morning is to find women who can cook and clean for the men in his nascent army. He later addresses what he considers a “minor problem”: “announcing to the half-dozen girls who had been rounded up that for the moment each would be permitted her parents’ hut for the night, but that in the future there would be no marriage permitted in the country save with his permission. He would expect them to choose their mates among his own men.” Later, when Philippe spots a Syrian caravan attempting to ford his river, he proposes robbing the merchants before downgrading his plan to merely extorting the heck out of them. Fitzgerald has a lurid preoccupation with how nasty and brutish people get when civilization shatters. He wants to shock and enlighten the magazine-reading public of 1935, like an Ivy League freshman who comes home at Thanksgiving and has grown so much wiser than everyone else.

Even so, “The Count of Darkness” isn’t just a retread of the previous story; Fitzgerald wants to dramatize setbacks in the campaign to renew the world. Philippe focuses so coldly on surveying land for a hill fort that he neglects the niceties that hold civilization together:

Catching the beast and saddling him, he pulled Letgarde up with him after he had mounted. The force of his pull almost wrenched her arm from its socket.

Smarting with sudden rage at the indignity, she waited in fright as, guiding the animal with his legs only, he next swung her about from a position facing him, to one that would later be called postilion. Furious and uncomfortable, she rode off behind him toward a destination of which she knew nothing. Perforce she clung to his body.

“Don’t let go, baby, and nothing can happen to you.”

Tasked with watching from a hilltop and signaling if she sees marauders, Letgarde bails:

He had scarcely gone galloping toward the other hill when Letgarde, quivering with indignation, set off on a dead run back to the wagons. She had never, from the most ruthless marauder, received such treatment—and she did not understand it. She came from a civilized province of old Roman Gaul. The Norse chief who had adopted her was little more than a sugar-daddy—he treated her always as a sort of queen.

But this man!

When Letgarde vanishes, rumored to have run off with a wandering singer, her memory haunts Philippe. He thinks he glimpses her, ghost-like and hateful, through the trees, and he can’t shake off a peasant’s story about “some nutsy girl down-stream that lives on a little island and thinks she’s Venus or something.” But in the midst of his obsessive fishing—a nighttime spear-hunt for eels that made me jot “Hemingway leaves Spain to fish in medieval France!” in my notes—he and his men behold a baleful sight:

Philippe’s voice was almost blasphemous on the dark tide, the lovely surface mirroring a round full moon, till—

“Oh my God in heaven!” he cried.

And then:

“Don’t you see?”

On the breast of the water rode the body of a girl; she was attired in only a shift, and for a moment she gave an appearance almost lifelike. Philippe pulled her into the glossy surface, illumined her by candles on the dark bank.

Philippe’s reaction is one of the only genuine surprises in this story. When a henchman reveals that Letgarde had been waiting desperately in this spot for the rain-swollen river to subside so she could cross, Philippe snaps:

Straight as straight, Philippe threw his ax at the man’s head. It hit, cleaved, biting deep, and Philippe went over with his sword and dispatched him. Then he turned to the others:

“Nobody told me this!”

Fitzgerald is on the verge of something noteworthy here: He’s taken the basic Astolat/Shalott motif, drenched as it is in medieval notions of love perfumed with Victorian romanticism, and made it unexpectedly useful in what could be a passable pulp yarn for early 20th-century men—and then he wrecks it. Letgarde’s avoidable death, Philippe’s fondness for her, his apparent liberty to murder his subjects in anger—Fitzgerald doesn’t let any of this resonate:

“When I got tough on you, you decided to go off with that gang—and you tried to find another ford? And you got stuck? And you got killed—so you wouldn’t have to come back to me!”

He picked up her body and rocked it to and fro.

“Poor little lost doggy—if you could have taken it a little better, you’d maybe be queen of these parts.”

Inert, her body slid from him; almost as inert, he retreated to a birch tree.

“She followed that damn’ tramp,” he thought, “just because I used her rough on the horse when I was in a hurry.”

By explaining everything, Fitzgerald leaves readers with nothing to do, no connections to make, no implications to ponder. When Philippe, “choked with emotion” and “lost in sorrowful contemplation,” meets an orphan outside his fort and adopts her as his own daughter, he tells his majordomo that the girl will be “sacred here forever”—and we’ve crossed the river into a weird new realm of hokey sentimentality.

“The Count of Darkness” does a poor job of making worthy points: Leadership is a burden, but its responsibilities include pragmatism and mercy, and warriors alone can’t bring civilization to fruition. Even amid chaos be mindful, Fitzgerald says, of the possibilities of love and affection, not just utilitarian arrangements, and remember that expediency is not necessarily wisdom. To that end, the story includes brief appearances by a wandering minstrel whom Philippe contemptuously calls a “hobo” and a “singing tramp.” At first I thought the singer was Fitzgerald’s way of suggesting how frivolous the arts must seem when people are starving, but maybe Fitzgerald felt similarly marginal as a writer in his own society by 1935, warbling lyrics in a world that has no use for them.

So far, Fitzgerald’s medieval stories have told me less about his perspective on the 1930s and more about his own fears. I thought he was using the Middle Ages only as a metaphor for the fragility of civilization, allowing him to trot out an example of the sort of rough man he believed could save or rebuild it, but his veer into sentimentality makes me think he found more in the past than his plan for the “Philippe” tales could accommodate. Most writers and artists who dabble in medievalism make their own highly selective version of the Middle Ages, the version they went looking for in the first place, but Fitzgerald wades into the ninth century and can’t make sense of things. That doesn’t necessarily make “The Count of Darkness” an interesting failure, but it does make it an honest one, underneath the kitsch.

Fascinating, although I am roiling in embarrassment!

And that’s a great critique. Ought to be handed out at Clarion and such workshops!

I like your suggestion that he went in with few pre-conceptions and plans and then found the world he found overwhelming… A story about that would be interesting.

LikeLike

I’m a little embarrassed for Fitzgerald too, but I hope these blog posts never veer into mockery. I’m hoping to learn something from these weak medieval-themed stories, maybe about Fitzgerald, maybe about American medievalism. I think I’ll look at the better pulp stories from the ’20s and ’30s with new respect now, too. And tonight I’m sitting down with the third of these four stories; we shall see what it has to offer.

LikeLike

No, I don’t think it’s mockery. But it certainly suggests that flitting from genre to genre does not work for everybody!

LikeLike

This entire series of posts has had me wincing – but indeed no, you don’t come off as mocking. Disappointed, but knowledgeable. Knowledge can be inconvenient, sometimes, when we read.

And even so, my interest in reading these for myself is only piquing/peaking. I mean, this was “my” area once, how could I not?

Thank goodness for you, on the point of American medievalism. It’s not all for naught, and that’s worth it, even beyond the curiosities these stories are. Gaining new respect for other works – and probably new perspective too, I imagine? – is also pretty cool. I absolutely love it when some other piece of information or experience informs some new entertainment. Life’s more resonant with layers like that.

LikeLike