Good news for a slow week: the latest ancient and medieval edition of Carnivalesque is up at Tiruncula. It’s a rich one this time; the links are heavy on the medieval, but folks who do ancient history will find plenty to interest them. (Plus there’s a cool picture of an owl, which is always a good sign.)

Month: September 2007

“And folded in this scrap of paper…”

What hath Nashville to do with Francia? Before this week, I might have answered “not much,” but that was before I discovered what may be the only country song that mentions the Emperor Charlemagne.

In “Charlemagne’s Home Town,” Texas-born James McMurtry becomes homesick while traveling abroad. During a pause in his travels, presumably at Aachen, he broods over an unresolved romance.

Near the end of the song, McMurtry lets his surroundings evoke the melancholy of the solo traveler:

Like the bones of some saint beneath a church floor

Who must have died for lack of light,

The color snapshots that I sent you

All came out in black and white.Won’t you fly across that ocean,

Take a train on down?

Because the night’s growing lonesome

In Charlemagne’s home town.

At Aachen, homesickness is a time-honored tradition. Countless ambassadors, dignitaries, messengers, and merchants went there during Charlemagne’s reign. More than a few must have pined for their homelands.

Although he didn’t travel to Aachen, Paul the Deacon nursed a similar sadness when he was forced to linger at Charlemagne’s court. In the 780s, the Lombard monk journeyed north across the Alps to one of Charlemagne’s palaces on the Moselle, where he petitioned the king to release his brother, a hostage. In a letter to Theudemar, abbot of Monte Cassino, Paul claims that the Frankish courtiers are friendly enough, but his mind and his heart are both elsewhere:

Even though the world’s vast distances physically keep me from you, a tenacious love for your companionship affects me; it cannot be severed. I am tormented nearly every moment by love for our brothers and superiors, to such an extent that it cannot be related in a letter or briefly explained in a few short pages.

For when I think of the times we devoted to such holy works; the most pleasant station of my quarters; your pious and religious goodwill; the troop of so many soldiers of Christ laboring to do holy works; the shining examples of diverse virtues in each brother; and sweet conversations about the Father’s highest kingdom, then I sit stunned, I am amazed, I grow weary, and I am unable to hold back my tears.

I dwell here among Catholics and dedicated Christians. They receive me well, and they show me sufficient kindness for your sake and for the sake of our father Benedict—but compared to your monastery, the palace is a prison to me, and compared to the great peacefulness of your community, life here is a hurricane.

This land holds only my worn-out body; in all my thoughts, where I remain strong, I am with you.

James McMurtry and Paul the Deacon wouldn’t have had much to talk about; the politically charged musician and the history-minded monk were born at the far ends of different and distant worlds. But by touching on the same essential emotion, the two men are commiserating across cultures, as lonely travelers have always done. Together they give voice to a fellowship of forgotten wanderers whose business brought them to Charlemagne but who dearly longed to be home.

This letter and song are a shared round of beer, even across 1,200 years. They’re also a reminder: sometimes the common ground is nothing more than the place where you happen to be stuck.

“Get to know the feeling of liberation and relief.”

Belgium was the antechamber of Charlemagne’s imperial palace—or so wrote Henri Pirenne, who was eager to defend his little country. I thought about Pirenne after reading this Economist editorial, which calls for Belgium’s peaceful dissolution:

A recent glance at the Low Countries revealed that, nearly three months after its latest general election, Belgium was still without a new government. It may have acquired one by now. But, if so, will anyone notice? And, if not, will anyone mind? Even the Belgians appear indifferent. And what they think of the government they may well think of the country. If Belgium did not already exist, would anyone nowadays take the trouble to invent it?

The anonymous editorialist tries to hit all the highlights of Belgian history:

Belgium industrialised fast; grabbed a large part of Africa and ruled it particularly rapaciously; was itself invaded and occupied by Germany, not once but twice; and then cleverly secured the headquarters of what is now the European Union. Along the way it produced Magritte, Simenon, Tintin, the saxophone and a lot of chocolate. Also frites.

Despite The Economist‘s irreverent tone, I was sorry to see that Pirenne wasn’t included on their list. Henri Pirenne belonged to the first generation of Belgian scholars to professionalize the study of history; he was central to promoting the study of social and economic history; and seven decades after his death, medievalists still debate his theories about the growth of towns and the effects of Islamic expansion on Europe.

Even so, talk of Belgium’s dissolution makes me remember not Pirenne the medievalist but Pirenne the Belgian citizen, a fellow whose scholarly work is best understood by acknowledging the extent to which his life and the life of his nation were often one and the same. When Germany invaded Belgium during World War I, Pirenne’s son Pierre died fighting for his country. Pirenne himself refused to re-open his university as a pro-German institution; he was imprisoned for 31 months. In one concentration camp, where he was the only civilian among officers from four nations, Pirenne lectured on medieval history; later, in a civilian camp, he helped to open a school. After the war, he returned to his work with a distaste for all things German—while never ceasing to cultivate a certain pleasant, persistent optimism.

A French-speaking Walloon, Pirenne married a woman who was half-Walloon, half-Flemish; together they had four children. Their family reflected the Belgian national motto, l’union fait la force, a unity that Pirenne honored, and implicitly advocated, in his massive, seven-volume Histoire de Belgique. He denied writing the series out of national pride: “I have written a history of Belgium as I would have written a history of the Etruscans,” he insisted, “without reason of sentiment or of patriotism.”

In public lectures and in print, Pirenne rejected German arguments that racial heterogeneity and the lack of a common language made Belgium “une nation artificielle”; he also answered critics among his own countrymen who advocated Walloon or Flemish secession. In his Histoire de Belgique, Pirenne described a modern nation that had emerged from medieval antecedents, and he argued that the Walloons and the Flemish were united through shared historic, economic, religious, and cultural experiences. Belgian history, he claimed, was a microcosm of European history and a product of peaceful collaboration, a point he stressed at an awards ceremony in 1912:

To the contrary, and thanks to the variety of its influences and its place at the most sensitive spot in Europe, [Belgium] presents the spectacle of liberal, welcoming, confident and generous activity, in which is found the best of what we Walloons and Flemish have produced together.

Critics of the Histoire de Belgique complained that Pirenne lingered over cases of Walloon-Flemish collaboration but downplayed, even ignored, conflicts between the two groups. Those conflicts were always more relevant, and more open, than he was inclined to admit. Although Henri Pirenne was a hero, celebrated in street names, honored with statues, and later commemorated on a postage stamp, the Belgian government stopped short of giving him a state funeral in 1935. Officials fretted that national honors at the Palais de Academies would be seen as an affront to the Flemish—the sort of awkward incident that Pirenne was likely to pass over in silence.

Both halves of Belgium are increasingly keen on going their separate ways. I’m no pundit, and I can’t fake an interest in Belgian politics, but if an amicable split occurs, I may feel wistful, if only on behalf of Henri Pirenne. With a peculiar, dispassionate patriotism, he argued for the existence of a civilisation belge. Come what may, his life will be proof that it existed.

“So I walk up on high, and I step to the edge…”

He told us about it our entire lives: the Hudson Toimnal, big as a city, born in Manhattan a year before he was. He could glimpse it by chance from his Gammontown stoop, or he could sneak to the rooftop for a better view, peering over three storeys of sooty clotheslines at the peaks of its twin towers. He later spent a decade there, twenty-six storeys up, crawling on beams over deep black shafts as he kept the elevators running.

He told us about it our entire lives: the Hudson Toimnal, big as a city, born in Manhattan a year before he was. He could glimpse it by chance from his Gammontown stoop, or he could sneak to the rooftop for a better view, peering over three storeys of sooty clotheslines at the peaks of its twin towers. He later spent a decade there, twenty-six storeys up, crawling on beams over deep black shafts as he kept the elevators running.

“That was some building,” he’d say, wiring up a toaster at the kitchen table, cracking a dead can opener in two. “They don’t make ’em like that no more.”

Shuffling to the cellar to study his switches and knobs, he hummed old songs through the few teeth left in his head. We heard the clack of the latch as he passed through the double doors, twin relics of his long-gone career. They were part of a Hudson Toimnal phone booth; he had hauled them home on a commuter train long before the towers came down.

He showed us his past in one fading brown snapshot: It’s 1934, and a skinny mechanic swings from rope-and-rag stirrups; he’s painting the northmost flagpole, a massive “U D S” behind him in awesome reverse. He’s only 25, but his smile says he’s the happiest man in Manhattan, with good reason: He’s hundreds of feet above the busy sidewalks, earning a rare day off from the best job he’ll ever have.

Sixty years later, the man in that photo surprised me. For all his talk about the Hudson Toimnal, he never expressed much interest in seeing its replacement—until one autumn morning, when he said that we should go.

As skyscrapers loomed over the deck of the ferry, I wondered what was happening at work.

“In them days,” he told me, “you wouldn’t dare take a day off. You take too many, they figured they could do without you.”

At the Battery, he gave a punk a cigarette and stared at the piers in confusion. “I don’t recognize none of this,” he insisted, but I pushed him through crowds of commuters and straight into the tourists. They were waiting to take the same elevator we were.

“I sure hope the cable doesn’t snap,” some jerk said, earning rueful snickers on the long ride up.

“Cables don’t break,” came the quiet rebuttal after we reached the top, “but if they do, the brake jaws grab the guide rails. That keeps the car from falling.” He was at home here, and still on the job.

But when we took the final escalator to the observation deck, he was silent for far too long. He studied the skyline. We were now a thousand feet higher than the flagpoles he had painted; all of it had changed.

Sad and lost, he shuffled his way to the western side. There he stopped, and began scanning for landmarks across the river—until, amazed to have sighted a familiar face, he rushed to a viewfinder, stuck in a quarter, and spun it straight toward the street where his childhood was.

He talked for weeks about what he’d beheld. “I thought the Hudson Toimnal Building was something,” he said. “But them Twin Towers…”

We heard less about the Hudson Toimnal Building after that, and for a while I forgot about the fading old photo. Five years later, I saw it again, in an envelope he left with my name on it.

Today, I keep it with a snapshot of my own: An old man visits a famous building that stands on top of his past. His hands grip the railing, as if a good gust might blow him away—but then he smiles, turns his ballcap backwards, and peers through the viewer, squinting to see where he’s been.

“So we go inside, and we gravely read the stones…”

Henry Adams was fond of statues. His 1904 book Mont Saint Michel and Chartres opens with Michael the Archangel “[s]tanding on the summit of the tower that crowned his church, wings upspread, sword uplifted, the devil crawling beneath, and the cock, symbol of eternal vigilance, perched on his mailed foot.” Later, when Adams notes a depiction of the Virgin Mary at the great cathedral of Chartres, he takes gentle, vicarious pleasure in imagining the twelfth-century mindset behind it:

The Empress Mary is receiving you at her portal, and whether you are an impertinent child, or a foolish old peasant-woman, or an insolent prince, or a more insolent tourist, she receives you with the same dignity; in fact, she probably sees very little difference between you.

Throughout Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, Adams plays the genial tour guide for his reader, whom he cheekily casts as his own wide-eyed niece. While the other faces of Henry Adams—novelist, academic, part-time Washingtonian, scion of a great political family—are shrouded by the author himself in the interest of efficient tourism, Adams the medievalist is a chipper fellow indeed. Faced with profundity, he is effusive, reactive, opposed to every pedantry. “To overload the memory with dates is the vice of every schoolmaster and the passion of every second-rate scholar,” he informs us. “Tourists want as few dates as possible; what they want is poetry.”

More than a century after its publication, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres is still a charming, imminently quotable work, an account of what happened when one of the sharper minds of late 19th-century America beheld the marvels of medieval France. I don’t know how well known the book is today, or how well regarded it is by scholars; I imagine it’s quite out of date. I do know that here in Washington, the influence of Henry Adams is most evident not at our cathedrals or in medieval history courses, but in a man-made grove at Rock Creek Cemetery—where, as Adams predicted, tourists seek poetry in a statue.

The tale of the statue is simple enough. Adams commissioned his friend Augustus Saint-Gaudens to create it in 1886, one year after his wife, Marian Adams, committed suicide. The larger structure later served as a tomb for both Marian and Henry Adams after the latter died in 1918, but the bronze figure became a tourist attraction even before Adams had seen it for himself. According to his third-person quasi-autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams, he hurried to the cemetery in 1892, as soon as he returned from Europe.

For readers who clung to the coat-tails of the avuncular tour guide of Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, the Henry Adams who visits Rock Creek Cemetery is unusually brooding and curt:

Naturally every detail interested him; every line; every touch of the artist; every change of light and shade; every point of relation; every possible doubt of St. Gaudens’ correction of taste or feeling; so that, as the spring approached, he was apt to stop there often to see what the figure had to tell him that was new; but, in all that it had to say, he never once thought of questioning what it meant.

Adams lets his reader infer the awkwardness of chatting with strangers who sought out the tomb of his wife:

As Adams sat there, numbers of people came, for the figure seemed to have become a tourist fashion, and all wanted to know its meaning. Most took it for a portrait-statue, and the remnant were vacant-minded in the absence of a personal guide. None felt what would have been a nursery instinct in a Hindu baby or a Japanese jinrickshaw-runner. The only exceptions were the clergy, who taught a lesson even deeper. One after another brought companions there, and, apparently fascinated by their own reflection, broke out passionately against the expression they felt in the figure of despair, of atheism, of denial. Like the others, the priest saw only what he brought. Like all great artists, St. Gaudens held up the mirror and no more.

Tourists to Rock Creek Cemetery still react in such strangely personal ways. During my visit there last weekend, I met a couple who had passed a few moments of sunny contemplation on the bench before the statue.

“She’s so beautiful,” the wife informed me. “She looks so hopeful—like she’s ready to cast off her shroud and fly.” When I told her about the suicide of Marian Adams, she seemed more bemused than troubled, reluctant to complicate her aesthetic experience with any newfound knowledge. Having cheerfully glanced into Saint-Gaudens’ mirror, she departed with an empty smile.

What did Adams see when he visited the cemetery? In the Education, he claims that the statue represented “the oldest idea known to human thought,” but his reader learns quickly to look past his loftier claims. The Education ignores the suicide of Marian Adams; in fact, it skips past twenty years, omitting the marriage entirely. Inclined to be silent rather than confess to sadness, Adams allows only traces of feeling to show. Perhaps his truest thoughts are better found elsewhere—in his defense of Norman architecture, for example, which, taken Adams-like and somewhat out of context, can be read as a case for the statue itself:

Young people rarely enjoy it . . . No doubt they are right, since they are young: but men and women who have lived long and are tired,—who want rest,—who have done with aspirations and ambition,—whose life has been a broken arch—feel this repose and self-restraint as they feel nothing else.

In his writing, Adams is an enigma: impressively learned, improbably modest, and always a little removed. He wanted that figure at Rock Creek Cemetery to be just as difficult to read—but each time he saw her, he hoped to discover something new. His books, although brilliant, will never reveal what he learned. To find the answer, you have to go: visit Rock Creek, sit across from that shrouded figure, and let her tell you about Henry Adams—not about his writing, wry and worldly and burning with praise for the archangel and the empress, but about the author and husband who finally ran out of words, and who counted on secrets that only a statue can tell.

“…to leave you there by yourself, chained to fate.”

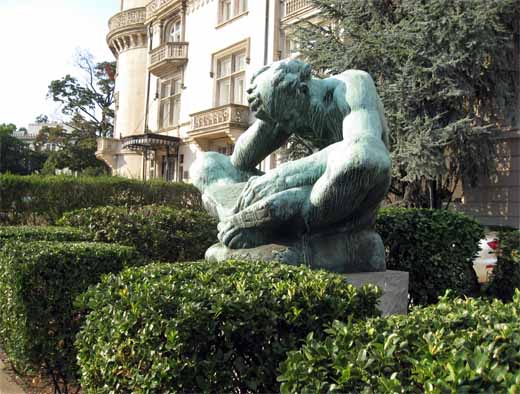

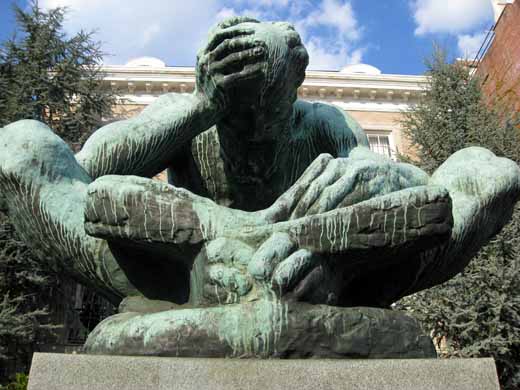

If you stroll along Massachusetts Avenue looking for inspiration on the day before school starts, you’ll encounter this figure at the Embassy of Croatia.

It’s Saint Jerome, who’s immersed in his work. If you’ve ever grappled with Jerome’s page-length Latin sentences, you’ve probably made this gesture, too.

For many of you, the coming weeks will call for much sighing and staring at tomes. Whether you’re a teacher or a student, here’s to a pleasant and productive semester—and not too much hieronymian clutching of the forehead.